In the heart of a dense forest, where sunlight filters through the canopy in dappled patterns, a quiet revolution in ecological research is unfolding. Scientists are now using advanced laser scanning technology to measure the daily fluctuations in tree photosynthesis with unprecedented precision. This phenomenon, dubbed "carbon pulsing," reveals how trees dynamically adjust their carbon uptake throughout the day—a discovery that could reshape our understanding of forest carbon cycles.

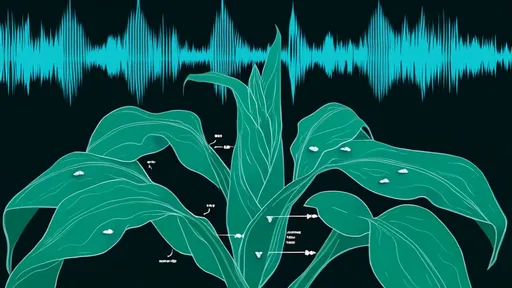

The traditional view of photosynthesis as a steady, continuous process has been upended by these new findings. Researchers armed with LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) systems have discovered that trees exhibit rhythmic patterns of photosynthetic activity, akin to a living organism breathing. These pulses occur in response to environmental cues like light intensity, temperature, and humidity, creating a complex symphony of carbon exchange that varies by species, age, and even individual tree health.

What makes this breakthrough particularly significant is its potential to improve climate models. Current estimates of carbon sequestration by forests may be significantly off because they don't account for these daily variations. "We've essentially been taking snapshots of a movie and thinking we understood the whole story," explains Dr. Elena Vásquez, a lead researcher on the project. Her team's work demonstrates that a tree's carbon uptake at noon can be 30-40% higher than during morning or evening hours, suggesting forests may be more dynamic carbon sinks than previously believed.

The technology behind these discoveries combines airborne laser scanning with ground-based sensors. Specialized LiDAR units mounted on drones or aircraft create detailed 3D maps of forest canopies, while spectrometer-equipped towers measure gas exchange at the leaf level. This multi-scale approach allows scientists to correlate structural features of trees—like leaf angle distribution and canopy density—with their photosynthetic performance throughout the diurnal cycle.

One surprising finding concerns deciduous versus evergreen species. While broadleaf trees show dramatic midday peaks in carbon uptake, conifers maintain more consistent rates throughout the day. This divergence appears linked to differences in leaf structure and water-use efficiency, challenging assumptions about which tree types are most effective at carbon sequestration under varying climatic conditions.

The implications extend beyond academic interest. Forest managers and carbon offset programs may need to reconsider planting strategies based on these daily patterns. A mixed-species forest with complementary photosynthetic rhythms could potentially sequester more carbon overall than monoculture plantings. Similarly, the timing of satellite measurements for carbon monitoring programs might need adjustment to capture these daily fluctuations accurately.

As climate change alters growing conditions worldwide, understanding these subtle biological rhythms becomes increasingly urgent. Early evidence suggests that heat waves and drought can disrupt normal carbon pulsing patterns, potentially making forests less reliable as carbon sinks during extreme weather events. The research team is now expanding their studies to different biomes to see how these patterns vary across ecosystems.

This laser-based approach represents a major leap from traditional methods like leaf chamber measurements, which could only sample small areas at discrete times. "We're essentially giving ecologists a new set of eyes," remarks Dr. Vásquez. "For the first time, we can watch the forest breathe across entire landscapes in real time." The team has already begun sharing their techniques with conservation groups hoping to monitor forest health more effectively.

Looking ahead, researchers aim to integrate these findings with satellite data to create global models of photosynthetic pulsing. Such models could dramatically improve predictions of how forests will respond to climate change—and how much carbon they can realistically remove from the atmosphere. In an era of climate uncertainty, these daily rhythms of the forest may hold keys to understanding our planet's future.

The study of carbon pulsing also raises philosophical questions about how we perceive plant life. The revelation that trees have measurable daily rhythms in their core biological function blurs the line between plant and animal behaviors. As one researcher noted, "We're finding that trees have their own version of a circadian rhythm—it's just expressed through carbon rather than movement." This perspective may influence how society values and protects forest ecosystems in the coming decades.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025