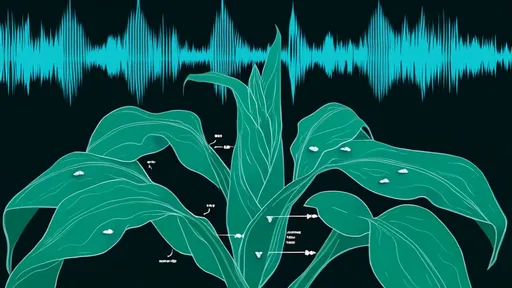

In the quiet hum of modern agriculture, a silent revolution is taking root. Researchers have uncovered an extraordinary defense mechanism hidden within one of humanity's oldest cultivated crops - corn plants emit ultrasonic frequencies when under insect attack. This discovery has sparked the development of revolutionary "Sonic Guardian" technology that could transform pest management practices worldwide.

The phenomenon was first observed when agricultural scientists noticed peculiar patterns in cornfield infestations. Certain varieties showed remarkable resistance to common pests like corn borers and armyworms without chemical intervention. After years of meticulous study using hypersensitive acoustic equipment, the team made their breakthrough - stressed corn plants produce distinct ultrasonic pulses between 35-55 kHz, frequencies undetectable to human ears but profoundly disturbing to many insect species.

Dr. Elena Vasquez, lead researcher at the International Crop Acoustics Laboratory, describes this as "plant language we're just beginning to understand." Her team's work reveals that different corn cultivars produce varying frequency patterns when attacked. The most effective natural deterrents emit complex modulated waves rather than simple tones, suggesting an evolutionary sophistication in plant bioacoustics previously unimaginable.

Building on these findings, agricultural engineers have developed prototype "Sonic Guardian" emitters that mimic and amplify the plants' natural defenses. Field trials across three continents show promising results - pest populations decrease by 40-60% without chemical pesticides when optimal frequency patterns are deployed. The technology works by creating an ultrasonic "discomfort zone" that deters insects from approaching while causing no harm to beneficial pollinators or other wildlife.

What makes this discovery particularly groundbreaking is the specificity of the effect. Unlike broad-spectrum pesticides that kill indiscriminately, the ultrasonic approach targets only pest species sensitive to particular frequencies. Researchers have created detailed "frequency optimization maps" showing which wave patterns work best against specific insects in various corn-growing regions. The Asian corn borer, for instance, shows greatest aversion to pulsed 42 kHz waves, while fall armyworms retreat from sustained 48 kHz emissions.

The practical implementation presents fascinating challenges. Soil composition, atmospheric conditions, and even the stage of plant growth affect how ultrasonic waves propagate through fields. Engineers have developed adaptive systems that modify frequency, amplitude, and pulse duration based on real-time environmental sensors. Some experimental models even "listen" to plants' natural emissions and respond with reinforcing signals, creating a symbiotic defense system.

Economic implications could be substantial for the $120 billion global corn industry. Traditional pesticide applications typically account for 15-20% of production costs. Sonic systems, while requiring initial investment, promise long-term savings and potentially higher yields as plants divert energy from chemical defense to growth. Early adopters in Iowa have reported 8-12% yield increases alongside reduced input costs.

Environmental benefits extend beyond pesticide reduction. The technology appears to strengthen plants' natural immune responses, making them more resilient to climate stressors. Researchers have observed secondary effects including improved drought tolerance and enhanced nutrient uptake in sonically protected crops. This unexpected bonus could prove invaluable as agriculture adapts to changing climate patterns.

As with any emerging technology, questions remain. The long-term effects of continuous ultrasonic exposure on soil microbiomes are still being studied. Some entomologists caution that insect populations might eventually adapt to the frequencies, requiring ongoing optimization. Regulatory frameworks for agricultural ultrasound use don't yet exist in most countries, presenting both challenges and opportunities for policymakers.

Farmers participating in trials express cautious optimism. "At first it seemed like science fiction," admits Carlos Mendez, a fifth-generation corn grower in Mexico's Bajío region. "But when I walked those silent fields at night and saw the moths avoiding my crops like some invisible wall stood between them, I knew this was something real." His experience echoes across test sites from Kenya to Ukraine, where the absence of chemical sprayers and the return of field birds provide visible confirmation of the technology's potential.

The research continues to expand beyond corn. Preliminary studies suggest wheat, soybeans, and even some fruit trees may possess similar acoustic defense mechanisms waiting to be harnessed. As the agricultural world stands on the brink of this bioacoustic revolution, one thing becomes clear - we've only just begun to hear what plants have been trying to tell us all along.

Commercial rollout of Sonic Guardian systems is expected to begin in select markets within two years, with full-scale deployment projected by 2028. As the technology develops, it may fundamentally change our relationship with crops - not as passive organisms we protect, but as active partners in ecological balance, whispering their secrets in frequencies we're finally learning to hear.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025